The Modernist period is replete with visions of a new aesethetics, a

new idea of what art and language ought to represent in a world drastically

different from any that came before. The basic argument of these theories

center around an attempt to reconsider, redefine, and recreate the role

of art in an world where everything (from humanity's origin to women's roles

in society) has been called into question. Most theories make reference

to the many cultural, scientific, and psychological developments which occured

during this period, including the work of Einstein,

Darwin, Freud,

and Edison. Many posit a correlation between the social changes brought

about by the heightened awareness of both physical and internal space. Many

even offer strategies through which art and language might be rethought

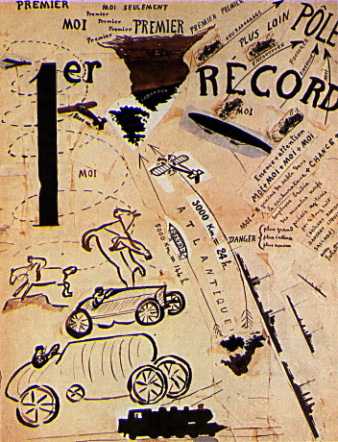

in order to better reflect modern life. Only Futurism, however, aligned

these theoretical frameworks with an enthusiasm for and fascination with

the machines of everyday life. As Marinetti outlines in "Technical

Manifesto of Futurist Literature":

Sitting on the gas tank of an airplane, my stomach warmed by the pilot's

head, I sensed the ridiculous inanity of the old syntax inherited from Homer.

A pressing need to liberate words, to drag them out of their prison in the

Latin period! Like all imbeciles, this period naturally has a canny head,

a stomach, two legs, and two flat feet, but it will never have two wings.

Just enough to walk, to take a short run and then stop short, panting! (M

92)

The language of Homer cannot fly; an airplane can. To create a language

that can fly, we must destroy Homer, "liberate words,"

and start again. This, briefly, is Marinetti's aesthetic theory. It is grounded

in a "lyric obsession with matter" (M 95), which replaces

"the ego of the writer, whose function now would be to shape the nets

of analogy that would capture elusive matter in the mysterious sea of phenomena."29

Instead of focusing upon subjective memories of the past, Marinetti offers

a Bergsonian vision of the time, a chain of sensations which produce a fragmented

and heterogenous notion of subjectivity. By destroying the pre-existing

conception of language, Marinetti attempts to redefine communication through

a dynamic ontology in which the past and present are continually becoming

the future. As he remarks in "Destruction of Syntax -- Imagination

Without Strings -- Words-in-Freedom":

Now suppose that a friend of yours ... finds himself in a zone of

intense life (revolution, war, shipwreck, earthquake, and so on) and starts

right away to tell you his impressions. Do you know what this lyric, excited

friend of yours will instinctively do?

He will begin by brutally destroying the syntax of his speech. He wastes

no time in building sentences. Puncuation and the right adjectives will

mean nothing to him. He will despise subtleties and nuances of language.

Breathlessly he will assault your nerves with visual, auditory, olfactory

sensations, just as they come to him. The rush of steam-emotion will burst

the sentence's steampipe, the valves of punctuation, and the adjectival

clamp. Fistfuls of essential words in on conventional order. Sole preoccupation

of the narrator, to render every vibration of his being. (F 98)

Language forces the flow of memories and sensations to adhere to particular

rules of syntax. The emotions generated from an event are, subsequently,

destroyed by sentences, puncuation, and proper narrative conventions. Futurism's

theory of language, on the other hand, attempts to destroy narrativity and

linearity, to allow words to explode into one another, thereby enabling

the energy and excitement of their content (that is, "life") to

appear without hindrance. Unlike the "discourse network of 1800,"

which rigidly separates words from noise, Futurism prioritizes the "half

word" or "gesture," thereby aligning signification not with

a transcendental "Truth" but with the physical body, which "becomes

a medium, a process, and enters into a system of energetic exchange that

will necessarily destroy it as an autonomous entity."30

Just as Bergson compares the workings of the human brain to a telephone

exchange, so too does Marinetti insist upon reading the human body as an

interface, a point of exchange that cannot function without a "double,"

or analogous concept; consequently, it is only in the encounter between

bodies that the "power" of Futurist language can fully emerge.

To this end, Marinetti's "Technical Manifesto" proposes the elimination

of all "colorful" or nonessential words such as adjectives, adverbs,

and conjunctions, in order to "free nouns from the domination of the

writer's ego."31 Puncuation, too, is

annulled because it slows down discourse; in its place Marinetti suggests

mathmatical signs (+ - x =) and musical symbols, which indicate direction

or intent, but do not interrupt the flow of language. Likewise, the infinitive

verb must be used exclusively, "because they adapt themselves elastically

to nouns and don't subordinate them to the writer's I that observes

or imagines" (M 92). Perhaps most significantly, Marinetti insists

upon "constant, audacious use of onomatopoeia," which, because

it "reproduces noise, is necessarily one of the most dynamic elements

of poetry" (M 109). Although onomatopoeia is an ancient poetic

technique, Luigi Russolo notes that "for centuries, poets did not know

how to make use of this very effective source of expression in language."32

This can be attributed to an unwillingness to fully exploit the "noise"

of consonants; as he remarks, "no noise exists in nature or life (however

strange or bizarre in timbre) that cannot be adequately, or even exactly,

imitated through the consonants" (AN 56). Words like "Trrrrrrrrrrrrrr"

to represent a speeding train, or "cuhrrrrr" to represent the

wheels of an automobile, bring an immediacy and directness to language,

and reinforce Futurism's goal of merging the everyday with the poetic.

Tying these syntactic rules together is Marinetti's conception of "analogy,"

or the layering of object upon object, noun upon noun, in an endless chain

of words, such as "man-torpedo-boat, woman-gulf, crowd-surf, piazza-funnel,

door-faucet" (M 92-3). These "words-in-freedom," as

he calls them, heighten the "natural" tendencies of human speech

in a world of increased speed and pespective (M 93), reproducing

"the rapport ... between poet and audience" or "between two

old friends," who "can make themselves understood with half a

word, a gesture, a glance" (F 98). Marinetti termed the analogic

process l'mmaginazione senza fili, which literally translates "imagination

without strings," but is commonly described as "wireless imagination."

The concept of the "wireless" is fundamentally different from

that of the phonograph, telephone, or conventional telegraph system, which

require a connecting wire or cable to maintain the communicative link. The

"wireless," as the name suggests, requires no such link, as the

signal itself is transmitted through the air from one receiver to another.

La Radia, the term which Marinetti and Pino Masnata gave "to

the great manifestations of the radio" 1933, is the ultimate symbol

of Futurist poetry, for it liberates words and speech from the confines

of bodies and projects them into a spatial theater that, because "no

longer visible and framable ... becomes universal and cosmic."33

The "universiality" of words, their inutterable connection with

the totality of life, represents Futurism's ultimate destination. This is

evident in the following example from Luigi Russolo's Arte Dei Rumori

(The Art of Noises), in which Russolo quotes from a letter written

by Marinetti "from the trenches of Adrianopolis," describing "the

orchestra of a great battle":

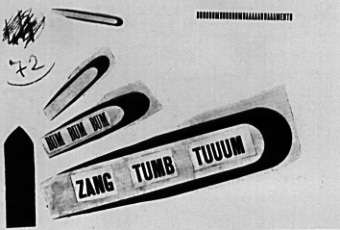

every 5 seconds siege cannons gutting space with a chord

ZANG-TUMB_TUUUMB mutiny of 500 echos smashing scattering it to infinity.

In the center of this hateful ZANG-TUMB_TUUUMB area 50 square kilometers

leaping bursts lacerations fists rapid fire batteries. Violence ferocity

regularity this deep bass scanning the strange shrill frantic crowds of

the battle Fury breathless ears eyes nostrils open! load! fire! what a joy

to hear to smell completely taratatata of the machine guns screaming

a breathlessness under the stings slaps traak-traak whips pic-pac-pum-tumb

weirdness leaps 200 meters range Far far in back of the orchestra pools

muddying huffing goaded oxen wagons pluff-plaff horse action flic

flac zing zing shaaack laughing whinnies the tiinkling jiiingling

tramping 3 Bulgarian battalions marching croooc-craaac [slowly] ...

(AN 26)

every 5 seconds siege cannons gutting space with a chord

ZANG-TUMB_TUUUMB mutiny of 500 echos smashing scattering it to infinity.

In the center of this hateful ZANG-TUMB_TUUUMB area 50 square kilometers

leaping bursts lacerations fists rapid fire batteries. Violence ferocity

regularity this deep bass scanning the strange shrill frantic crowds of

the battle Fury breathless ears eyes nostrils open! load! fire! what a joy

to hear to smell completely taratatata of the machine guns screaming

a breathlessness under the stings slaps traak-traak whips pic-pac-pum-tumb

weirdness leaps 200 meters range Far far in back of the orchestra pools

muddying huffing goaded oxen wagons pluff-plaff horse action flic

flac zing zing shaaack laughing whinnies the tiinkling jiiingling

tramping 3 Bulgarian battalions marching croooc-craaac [slowly] ...

(AN 26)

The "bursts" of sensations and energies theorized in Marinetti's

manifestoes emerge in this letter through the description of noises, gunfire,

and troop movement, which render the experiences of war as visible, audible,

and tangible as language will allow. The use of "words-in-freedom,"

such as the string "orchestra pools muddying huffing goaded oxen wagons,"

effectively replicates the rapid array of sensations and impressions that

Marinetti experienced on the battlefield. Likewise, the use of onomatopoetic

words such as "taratatata" and "pic-pac-pum-tumb," to

describe shell bursts, troop movements, and other actions, add an immediacy

to the letter, thereby heightening the representation of "life,"

which was central to Futurism's aesthetic designs. All the same, it is important

to note that Marinetti was attempting to put into written language the sounds

of a battle; as such, his efforts can only attain a certain resemblance

to the lived experience. In other words, Marinetti is dependant upon the

technology of writing, both the physical limitations of the written page

and the need to retain a certain narrative cohesiveness -- that is, to make

sense to his readers. This is most evident in the linear structure of the

above letter: a scene is set (battlefield), characters parade in and out,

action ensues, and a resolution (in the form of the transformative effects

of war) is realized by the writer. This consequence of writing was not lost

on Marinetti, whose gave a cautionary analysis of his own system: "When

I speak of destroying the canals of syntax, I am neither categorical nor

systematic. Traces of conventional syntax and even of true logical sentences

will be found here and there in the words-in-freedom of my unchained lyricism"

(F 99). Marinetti later notes that "We ought not ... to be too

much preoccupied with" Futurist language, "But we should at all

costs avoid rhetoric and banalities telegraphically expressed" (F

99). Futurism can only mutilate language so far; in the end, traditional

mores and attitudes are retained.

In many ways, the failures of Futurist writing are not uncommon among the

early modernists, most of whom have disappeared from bookshelves and are

almost entirely forgotten except for the movements they helped create. Certainly

most scholars of "modernism" attest to the aesthetic insignificance

of Futurist art, from their poetry and drama to their plays, music, dance,

cinema, and architecture. While this debasement is largely attributed to

the artistic inabilities of its participants, one can also cite the contradiction

at work in Futurism's dual goal of destroying all shreds of a historical

and artistic heritage while simultaneously attempting to create a new system

of knowledge and "truth" based upon an aestheticization of the

machine. In order to create this "future," Futurism necessarily

employed the same artistic mediums (print, painting, etc.) which characterize

the past. By and large, Futurist work that is most often cited for its originality

and creativity are the works that most consistently reproduce the sensations

and emotions of everyday life in a mechanized world. These include Marinetti's

prose-poem/manifestoes, which aestheticized "a new typographic format,

a format drawn from the world of advertising posters and newspapers,"

and in which "the page supplants the stanza or the paragraph as the

basic print unit";34 Futurist performances,

which introduced the concept of "multi-media" spectacles, simultaneously

combining poetry, theater, dance, cinema, painting, and political debate

within a single space; and, perhaps most significantly, Luigi Russolo's

The Art of Noises, which redefined music not as a product of the

concert hall but as a cacahophony of everyday sounds, from engines and busy

streets to factory whistles and machine guns.

WebGlimpse |

|

| Search: The neighborhood of this page The full archive | |