The Eternal Recurrence of "l'effroyablement ancien" excerpted from "The [Convulsive] Enigma of Eternal Recurrence in de Chirico's `Architecture,'" (1998)1 Thomas Mical2 |

|

De Chirico's "metaphysical" representations of architecture (1910-1917) reiterate repetition and recurrence as a disturbing "alterior" history, a dis(re)membered Nietzschean classicism of "awe, joy, and terror" suspended in proximity to modern figures and representation. As both a supplement to the discourse of architecture, and as an interruption, the paintings executed by de Chirico in the "metaphysical" period position architecture as a "disquieting" subject matter, transgressing the traditional representation of architecture as knowable, measurable, and reactive to context and chronology. The potential effect of architecture to radically disrupt the stable and rational foundations of the subject, and its repetition in the "metaphysical" work becomes the basis for recuperative theory of the unspoken and unhinging origin and end of architecture as "l'effroyablement ancien"(the terrifyingly ancient).

Concerning origins, Tafuri returns to Foucault, who returns to Nietzsche:

In posing the problem of an 'origin,' we presuppose

the discovery of a final point of arrival: a destination point that

explains everything, that causes a given 'truth,' a primary value,

to burst forth from the encounter with its originary ancestor. Against

such an infantile desire to 'find the murderer,' Michel Foucault has already

counterpoised a history that can be formulated as a genealogy: 'genealogy

does not oppose itself to history as the lofty and profound gaze of the

philosopher might compare to the mole-like perspective of the scholar;

on the contrary, it rejects the metahistorical deployment of ideal significance

and indefinite teleologies. It opposes itself to the search for 'origins.'3

"The insignificance of the origin increases with the full knowledge of the origin."4

Foucault offers "the origin lies at a place of inevitable loss, the point where the truth of things correspond to a truthful discourse, the site of a fleeting articulation that discourse has obscured and finally lost."5

In de Chirico's architecture, and perhaps in all discourse, the origin merely conceals another origin. The origin as locus of truth and source of the discursive power of history is a contrivance of reason under the spell of Socratic time.6

History itself is rendered nonsense in the thought of eternal recurrence; origin and end become fleeting vanishing points.

How then to begin? Genealogically, to go beyond de Chirico we must go before de Chirico, before the origin/s. In the absence of the origin, Deleuze wishes for an originary point:

Ö the point at which the ultimate origin

is overturned into an absence of origin (in the always displaced circle

of eternal return). An aleatory point is displaced through all the points

on the dice, as though one time for all times. These different throws which

invent their own rules and compose the unique throw with multiple forms

and within the eternal return are so many imperative questions subtended

by a single response which leaves them open and never closes them.7

"The origin of that which has no origin is the origin of the work of art."8

De Chirico's representation of architecture is close to the Derridean supplement that masks this impossible origin:

the infrastructure of supplementarity, by knotting

together into one structure the minus and the plus, the lack of origin

and the supplementation of that origin, does not choose between either

one of them but shows that both functions are dependent on one another

in one structure of replacements, within which 'all presences will be supplements

substituted for an absent origin...'9

THE VISION OF ETERNAL RECURRENCE, THE FIRST TIME

The vision of eternal recurrence the first time is an unhinging vision: Waite postulates, "Nietzsche's own first encounter with his 'thought' apparently had the force of an inarticulate traumatic experience."10

Klossowski reads the unpublished search for scientific proof of the doctrine of recurrence as Nietzsche's attempt to disprove madness: "for this idea to be both horrible and exhilarating, there was also a second factor... for who was capable of receiving such an idea? Only a delirious intelligence."11

This irrational thought is more than a thought - it is a profoundly disturbing effect for Nietzsche, unhinging and unable to be reasoned away. Nietzsche's "greatest weight" actively "suspends the very principle of reality."12

Bataille writes

Nietzsche's thought, which resulted in the sudden

ecstatic vision of the eternal return, cannot be compared to the feelings

habitually linked to what passes for profound reflection. For the object

of the intellect here exceeds the categories in which it can be represented,

to the point where as soon as it is represented it becomes an object of

ecstasy - object of tears, object of laughter.13

Klossowski reiterates this oscillation of reactions to this convulsive thought, founded upon the suddenness (the stopped time) of this unhinging vision (like the suddenness of iron filings snapped into place instantly by a concealed magnet):

In short, the Eternal Return, originally, is not

a representation, nor a postulate proper, it is an experienced fact and

as thought, a sudden thought: phantasy or not, the Sils-Maria experience

exercises its constraints as ineluctable necessity: terror and mirth in

turn, within this felt necessity, will underlie from this instant Nietzsche's

interpretations.14

"Bataille here names the ecstatic experience suffered by Nietzsche l'expérience intérieure."15

""Inner Experience is no more an experience than it is inner;" as it is always in excess - "thus that which Nietzsche named the eternal return has nothing fundamental about it: based on it, nothing is fundamental any longer, it is the loss of a foundation, the irruption of the bottomless."16

Klossowski's research examines this vision of eternal recurrence the first time from immediacy and surprise, asking, after Nietzsche - what am I at the instant I am seized by this thought?17

The answer is an alterity, "otherness," - for Klossowski this terrifying thought constitutes a multiple alterity of the self, a perpetual metamorphosis.18

The Eternal Return is in a way simply the mode

of its display: the feeling of vertigo results from the once and for

all in which the subject is surprised by the round of innumerable

times: once and for all disappears: intensity emits something like

a series of infinite vibrations of being: and it is these vibrations which

project outside itself the individual self as so many dissonances:

all reverberate until is re-established the consonance of this same instant

in which these dissonances are reabsorbed anew.19

Kaufmann is the first interpreter to write this enigma in proximity to the body: "to understand Nietzsche it is important to realize how frightful he himself found the doctrine and how difficult it was for him to accept it. Evidently, he could only endure it by accepting it joyously, almost ecstatically. That is what he said more indirectly when he finally presented the idea in 'the greatest weight.'"20

Nietzsche's troping of weight is clarified by Kundera, who contends, "in the world of eternal return the weight of unbearable responsibility lies heavy on every move we make. That is why Nietzsche called the idea of eternal return the heaviest of burdens (das schwerste Gewicht)."21

Weight (and severity), a heaviness posited by Parmenides as the negation of lightness, is reversed in the "spirit of gravity" of eternal recurrence. Here "the question of weight or lightness is not insignificant. To the contrary, it is the question of significance itself. Meaning presupposes iteration - what recurs is significant (weighty) and what does not is insignificant (immaterial)."22

"The only certainty is: the lightness/weight opposition is the most dangerous, most mysterious of all."23

Lightness and heaviness, ascending and descending, these degrees of tethered-ness to time's passage eternalized in the vision of eternal recurrence the first time allow this vision to isolate and identify the body as the primary ground of eternal recurrence. Gravity and perishing temporality (previously external to the body) are reconfigured as the interior forces of this convulsive thought.

The significance of this sudden vision for Nietzsche was also both instantaneous and lasting: "immortal is the moment in which I engendered the Recurrence. For the sake of this moment, I endure the Recurrence."24

Nietzsche later wrote "if it is true, or rather: if it is believed to be true - than everything changes and spins around, and all previous values are devalued" and "when you incarnate the thought of thoughts, you will be transformed [verwandeln]."25

Eternal recurrence comes as possession: Nietzsche believed "if this thought gained possession of you, it would change you as you are, or perhaps crush you."26

This partially explains why the "anxiously shaken and secretively cautious way in which Nietzsche's letters and notes report on the emergence of 'his' idea. This idea is at first not conceived, but rather is an ecstatic 'experiment in thought'..."27

"In his letters to Gast and Overbeck, written shortly after the event, Nietzsche, without betraying the thought of thoughts, was already speaking of the effect its disclosure would produce... its disclosure would break the history of humanity in two."28

This vision of eternal recurrence searches for words; a riddle that "can't be asked twice," eternal recurrence is always a symmetrical enigma (of origins, identity, and time).29

The distinction between the experience (vision) and thought of eternal recurrence is that of a "first time" and a "not the first time."30

The primacy of the unhinging vision repeated in the text as a search for its effect places forgetting at the center of this speaking, a forgetting of the same species preceding the "first time": "I had to forget that revelation [of the eternal recurrence] for it to be true."31

This "anamnesis coincides with the revelation of the return: how does the return not bring back the forgetting?"32

Eternal recurrence (the first time), a forgetting of the self, predicated on a historical-self awareness, is a sudden forgetting of origins. In Nietzsche's first "convulsive" vision, this forgetting is a forgetting also of the origins and history of the thought itself.

To experience this unhinging thought of eternal recurrence the first time, Nietzsche forgets the impossible origin(s) of this thought though there is a "bewildering array of candidates for ancestors" to the thought of eternal recurrence.33

When Klossowski writes ""isn't forgetting the source and indispensable condition not only for the appearance of the eternal return but for transforming the very identity of the person to whom it appears?" it is implicit that this self (Nietzsche) must also forget the previous known models of recurrence for it to occur "the first time."34

"Nietzsche defines the faculty of forgetting as 'no mere vis inertiae as the superficial imagine; it is rather an active and in the strictest sense positive faculty of repression', 'an apparatus of absorption', 'a plastic regenerative and curative force'."35

This "memory that knows how to forget" consumes its origin(s), to make itself original.36

Klossowski notes "to adhere to the return

is also to admit that forgetfulness alone enabled us to undertake old creations

as new creations ad infinitum." - including the unique identity

of the "terrible thought" itself.37

In the Stoic doctrine of ekpyrosis, this world ends as it begins, in a total (apocalyptic) fire. The subsequent world that returns will be identical to the prior, the same necessary and fated events repeat as new only within their world-cycle. This conflagration in fire is the periodic return of ekpyrosis, the interval between its return the "great year." There is no "time" in any meaningful sense before or after the world-cycles of this cosmology.38

Its genealogy is traced in Nietzsche's time to

the (lost) writings of Heraclitus.39

"Fire, having come suddenly upon all things, will judge and convict them" - for Heraclitus fire consumes all; "cosmic justice and symmetry require that at some point all things return to the source from which they emerged."40

The instability of fire, its apparent caprice and metastatic power is in Heraclitus localized in the tropai of fire, their irrational turning points.41

Nietzsche writes "before his eye not a drop

of injustice remains in the world poured all around him... it constructs

and destroys, all in innocence... from time to time it starts them anew...

such is the game that the aeon plays with itself."42

How? Heraclitus writes "the beginning and the end are shared in the circumference of a circle," and this is read by Nietzsche (and his interpreters) as an esoteric figure of time.43

This possibility of time cannot remain linear (teleological, transcendental, rooted in Being), metaphorical machinery of the universe - "the path of the carding wheel is straight and crooked."44

The time of the world is a difficult proposition in this world of "becoming," exemplified in Heraclitus' most cited fragment: "one cannot step twice into the same river, nor can one grasp any mortal substance in a stable condition, but it scatters and again gathers; it forms and dissolves, and approaches and departs."45

The young Nietzsche initiates a lifetime affinity for this revelation: "Heraclitus will always be right in this, that being is an empty fiction."46

Being, initiated by Parmenides, contra Heraclitean becoming. Within Heraclitean becoming there is a premonition of Nietzsche's later experience of eternal recurrence the first time: "the everlasting and exclusive coming-to-be, the impermanence of everything actual, which constantly acts and comes-to-be but never is, as Heraclitus teaches it, is a terrible, paralyzing thought."47

Paralyzing because in Heraclitus it is the irrefutable (game-like) "innocence of becoming" - that nothing is intended by becoming.48

Voided teleology = voided metaphysical time = "the labyrinth of recurrence."

NIETZSCHE'S "CLASSICAL" LABYRINTH: APOLLONIAN RECURRENCE

If Nietzsche's decision against everything previously

believed in is an explosive that breaks in two the history of European

humanity so far, he harks back (in anticipation of the history that comes

after him) behind the history that precedes him,'with a voice that bridges

millennia.' Accordingly, in Twilight of the Idols he explicitly

attributes his teaching to what he 'owes the ancients.' Therewith he repeats

the 'tragic mentality' of antiquity; the restoration and 'transposition'

of that mentality into a philosophical pathos was already the theme of

The Birth of Tragedy and of Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the

Greeks. By means of this return to the old world, Nietzsche thought

he had found the exit 'from whole millennia of the labyrinth.'49

This labyrinth of time broken by the return of the classical is itself a classical construct, in that its entrance and exit are the same. The early Greek model of recurrence is turned (reversed) in Nietzsche: the classical is the distant exit to this (modern) labyrinth. Duplicating the structure and function of eternal recurrence, the Nietzschean "classical" returns to overturn the labyrinth it originated.

Within the classical, three modes of representation recur: epic, lyric, and tragic. Weiss claims "the eternal recurrence is the extreme epic philosophy... a cosmic therapy against the terror of the passing of every moment, a vanishing into nothingness, into absolute oblivion."50

Kundera identifies two possible interpretations (of eternal recurrence) as epic and lyrical, but he excludes the mode closes to the early Nietzsche, the tragic mode.51

The promise of Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy is the return of the tragic to occupy the center and exit of this labyrinth. From this text "European intellectual history thus appears as the ebb and flow of a single motif that circles around or undulates between ascent, descent, and return."52

The Birth of Tragedy "is not only a manifesto on the polarity between the Apollonian and Dionysian artistic drives, but is itself the result of the interplay of energies that are both raging and resistant, intoxicating and precise."53

The Apollonian is "representation and formalism' in the mode of repetition; it "dissimulates the terrors of the Dionysian abyss..."54

Tragedy is a "monstrous" relation between these two images of the gods.55

"In truth, the polarity between Apollo and Dionysus is not a turbulent opposition that vacillates freely between two extremes; we are dealing much more here [tragedy] with a stationary polarity that leads to a clandestine doubling of the Apollonian."56

This doubling of Apollo is also the doubling of his effects.

Apollo "adjusts distances to things," he is "a cold, always-distant god, the god of the horizon, the god of the far-reaching gaze."57

Apollonian time is horizontal, smooth, cold and reflective, a distancing of time tending towards the absolute degree zero of the spacing of time (as it was in the beginning). The horror of eternal recurrence is a question of duration.58

Apollonian time is also the time of the immobile

labyrinth - time is stopped, emptied, deferred - tending towards eternity.

It seizes and posses by vision, though only the self-same vision returns,

the mask of Apollo returning the image of Apollo. Within this labyrinth,

the self searches for an exit from the horrors of time, for a true fate.

In the "coils" and "loops" of the labyrinth of Apollonian

recurrence, every move is a fatal move.59

The manifold detours between interiority and exteriority, between the moment-interval and eternity are the labyrinthine effects of the thought of (Apollonian) recurrence. The construction of time that returns to return the self to the beginning is this labyrinth that Nietzsche names "circulus vitiosus deus."60

This vicious circle "suppresses every goal and meaning, since the beginning and the end always merge with each other;" "there is no point of the Circle that cannot be beginning at the same time as end.;" it "is grounded in the forgetfulness of what we have been and will be."61

Within this circle, what is forgotten? That everything must return - the "possibility of "lightness" is exiled outside the labyrinth, and also everything that would prevent eternal recurrence from seizing the self for "the first time."

Blanchot, speaking in a fragmentary writing, states: "the 're' of the return inscribes as the 'ex', opening of all exteriority: as if the return, far from putting and end to it, marks exile, the commencement in its recommencement of exodus. To return, that would be to return again to ex-centering oneself, to erring. Only the nomadic affirmation remains."62

This detouring of the labyrinth is written by Nietzsche as a (double) recoil:

In Nietzsche's writing... we find a double recoiling

action: there is the claimed eternal recoiling again of each event before

it springs forward again, expending itself, burning out and slowly coiling

again in an unthinkable return of life force to the event's constellation;

then there is the coiling again in the claims of the eternal and the return,

of the early Greek image of time, the conflict of meaning and meaninglessness,

the peculiar Western anxiety over death and loss, the twin anxieties of

keeping and releasing... these composing elements are coiled again in Nietzsche's

metaphor [the return as a circle].63

Within the labyrinth of recurrence, the circle circumscribes the question of the identity of the self, as Blanchot contends: "the circle, uncurled along a straight line rigorously prolonged, reforms a circle eternally bereft of a center."64

Recurrence can never be a simple circle.65

Klossowski reads this void in the core of recurrence as existence without signification: "the circle opens me to inanity and encloses me within the following alternative: either all returns because nothing has ever made any sense whatever, or else things never make any sense except by the return of all things, without beginning or end... by itself, the circle says nothing, except that existence has sense only in being existence, or that signification is nothing but an intensity."66

Apollo, the labyrinth, circles and recurrence are

each avatars of an intense Nietzschean "classicism," which originate

and end the question of time. Eternal recurrence of the (classical) past

is, for Deleuze, therefore not an impossibility of passage but "an

answer to the problem of passage."67

The Apollonian labyrinth conceals a "terrible" secret at its center. The (architectural) instruments of repetition, exteriority, and emptying construct this architecture of the self's place in time - as a vertiginous depth. The center is the origin of erosive time. Time here means "in time," in the devouring that is time.68

Bataille's reflection on this depth in the Nietzschean revaluation of time is in the words of this labyrinth's center:

[before the idea of eternal recurrence] only the

object of his vision - which made him laugh and tremble - was not the return,

but what the return (and not even time), but what the return laid bare,

the impossible depth of things. And this depth, should one reach it by

one path or another, is always the same... perceiving it, there is nothing

left to do but collapse (become agitated right to the point of fever, lose

oneself in ecstasy, weep).69

The center is the place of the spirit of gravity (of time's labyrinth). In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in a section entitled "The Vision and the Riddle," the "spirit of gravity" has words, it speaks that "time is a circle."70

Zarathustra seeks a more exact answer, proposing that at the threshold called moment, two eternities extend beyond the horizon, one past, one future, indistinguishable - eternity is horizontal (Apollonian). The vertical must be the moment, the pure interval; they cross at the center of the labyrinth, in the shape of the chiasmus. Paradox, aporia, inversion of opposites do not describe the severity of this improbable crossing.71

What lies beneath the center of the labyrinth, what is marked by the "x" that originates the labyrinth of time? "Nietzsche thinks that our experience of time as succession has its root in our fear of destruction. Trying to avoid death, we play for time."72

This insight finds its echo in Freud's later Beyond

the Pleasure Principle, where from a condition of "perpetual recurrence

of the same thing" he identifies the function of repetition, "these

circuitous paths to death, faithfully kept to by the conservative instincts."73

THE MOMENT/UM OF REPETITION

In the eternal recurrence the "eternalized" moment is "intensified" as "a standing together of temporal moments" convulsively in the "horizontal axis of succession" of eternity.74

The moment, thus configured spatially, posits the inseparability of spatial and temporal possibilities (as does the labyrinth of the "classical," in recurrence). The possibility of eternity, as an exteriority that interrupts the moment of interiority, is unstable in Nietzsche's writings, appearing as "endless duration," an "eternal present," the "simultaneity of all moments," or as "timelessness."75

Eternity "is that in which occurrence ends";

in Nietzsche's "great thought" the moment ends vertically into

eternity.76

The totality of moments, like the totality of

spaces, is not extensively infinite, even though the displacement of moments

never ceases..." and thereby implies "that there is a colossal

depth to each moment, which multiplies its significance to infinity. Instead

of thinking of time as merely successive - what might be called the 'horizontal'

conception of it - Nietzsche's vision of a recurrent universe leads us

to think of it also as 'vertical.' This is shown in his frequent references

to the 'well.'77

Nietzsche's depictions of the "well of eternity" impart a "quasi-vertical dimension to each moment" and "opens up the possibility of depth, and, experientially, intensity."78

Eternity intersects the moment, eternalizing it, not as a doubling of time, but as an instantaneous eruption of time, an arising and perishing of instants without procession, effects a self-consumption of moments without goal.79

"Eternal recurrence seems merely to be a very powerful modification or extension of seriality...."each individual moment acquires membership of an additional, transversal series [vertical depth]."80

Deleuze writes "and what would eternal return be, if we forget that it is a vertiginous movement endowed with a force: not one which causes the return of the Same in general, but one which selects ...Nietzsche's leading idea is to ground the repetition in eternal return on both the death of God and the dissolution of the self."81

That which the eternal recurrence extends (eternalizes) is the moment/um of repetition, as when Nietzsche writes "if only one moment of the world recurs - said the lightning - all moments must recur... whoever wants to have a single experience again, must wish for everything again."82

Repetition is the return of the "untimely" from the well of eternity (in the labyrinth of eternal recurrence) prohibiting both stasis and closure "by willing the never-ending repetition of finitude and time, no longer seeking a ground in absolutes beyond the negativity of the world-processes."83

"Reconciliation with time occurs as willing back. This could mean either of two things: (1) to will backward into time, so to speak, turning time around, reversing it, or (2) to will things and events back, to will them to come again, to return."84

To the old irreversibility of time, Nietzsche proposes "Zarathustra's remedy: to re-will the non-willed insofar as he desires to assume the accomplished fact - thus to render it inaccomplished, by rewilling it innumerable times.85

"In the case of Nietzsche: liberate the will

from everything that binds it by making repetition the very object of willing."86

In this aspect of eternal recurrence, the relations of past and present, within the moment, are no longer categories of time but instruments of repetition. "He who repeats so that time will come back has already separated himself from time."87

Nietzsche writes

[in] Greek thought... repetition is erroneously what one calls 'mediation'...for what is repeated, has been; otherwise, it could not be repeated; but precisely the fact that it has been, makes the repetition into something new... repetition is the interest of metaphysical and at the same time the interest on which metaphysics founders.88

It is the clothing that cannot be worn out.89

Eternal recurrence is Apollo expressing Dionysus, therefore recognizing appearance as appearance, and itself as appearance. But what distinguishes eternal recurrence from Greek tragedy is that eternal recurrence explicitly recognizes and reveals the eternal value of appearances, i.e. as repeatable.90

Blanchot concludes that the moment of eternal recurrence is the "moment when logos comes to an end - affirming itself and always new again without novelty, through the obligation - the madness - of repetition."91

Deleuze, in Difference and Repetition, exhaustively thinks through the thought of repetition bound to the question of eternal recurrence: "repetition is a condition of action before it is a concept of reflection."92

Initially, originally, "the form of repetition in the eternal return is the brutal form of the immediate."93

Deleuze contends the old linear notion of time that "distributes a before, a during, and an after... is already repetition in itself, in the pure form of time... repetition no longer bears (hypothetically) upon a first time which escapes it, and in any case remains external to it..."94

In the irrational "law" of eternal recurrence,

repetition is not "secondary in relation to a supposed ultimate or

originary fixed term," but present at the origin, before the origin:

"the before or first time is no less repetition than the second or

third time."95

After Nietzsche, (Nietzsche's who speaks in double-figures), repetition is two. Following from Freudian repetition, under the aspect of "perpetual recurrence of the same thing," repetition is originally "habitus... repetition as a binding" and secondarily "Eros-Mnemosyne... repetition as displacement and disguise."96

Original repetition "is prolongation, continuation, or that length of time which is stretched into duration: bare repetition."97

Clothed repetition is "the reprise of singularities, the condensation of singularities one into another... repetition is this emission of singularities."98

From these two repetition Deleuze announces the "third repetition or repetition within the eternal return ... it is here that the freeze-frame begins to move once more, of that the straight line of time, as though drawn by its own length, re-forms a strange loop which in no way resembles the earlier cycle, but leads into the formless..."99

This third repetition of recurrence is "repetition by excess which leaves nothing intact... it is by itself the third time in the series, the future as such... as Klossowski says, it is the secret coherence which establishes itself only by excluding my own coherence, my own identity, the identity of the self."100

Deleuze acknowledges "if repetition exists,

it expresses... an eternity opposed to permanence. In every respect, repetition

is a transgression."101

Repetition in a series produces an effect of detouring and uneasy signification - the repetition of an act or scene creates doubles it as both scene and representation (signifier). This signification through repetition becomes a secondary (alterior/anamorphic) repetition.102

The self is rendered as alterior, as tending towards anamorphosis, in the repetition(s) of recurrence. Deleuzian (neo-Nietzschean) repetition is opposed "to particularities of memory... it is in repetition and by repetition that forgetting becomes a positive power."103

Forgetting is also the forgetting preceding and produced by eternal recurrence. Put simply, repetition invokes eternal recurrence through repetition and remembering.

Freud, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, thinking not of eternal recurrence but of repetition as an abnormal compulsive behavior, begins with a distinction between (pathological) repetition and (casual) remembering.104

This text identifies the compulsion to repeat as a wish to conjure up what has been forgotten and repressed, told as Nietzsche would, through a parable.105

The fable of "fort-da" is an old story. Freud's insight into the "fort-da" experience, as the experience of loss and the mastery over loss through repetition (as compulsion) echoes Nietzsche's (and de Chirico's) willing of the return of the "classical" - the "classical" is their repetition-compulsion. Tafuri and Teyssot write, "classicism is the art of the eternal recommencement, of repetition and synechdoche.106

The proper repetition-compulsion "serves to present and represent the repressed through content by proxy, through indirection, through oblique reflection, through the cast and casting of shadow play, through the mask of disguise..."107

These terms recur in Nietzsche's writing of the (tragic) "classical," symptomatically. Repetition, as signification and obscurity, is bound to language with an immediacy that eternal recurrence is not. After the fort-da observation of loss, the (Freudian) compulsion to repeat is a compulsion to metaphor.108

In Freud, the compulsion to repeat is also a compulsion of destiny.109

In Nietzsche, it is a compulsion to destiny. He writes, "the moment is immortal where I produced return. For the sake of this moment I bear the return."110

Beyond the Pleasure Principle thinks towards an unanticipated conclusion, that instinctive repetitions an urge towards the "old state of things," the initial state or origin that is identified as death (thanatos).111

"Life under the sign of the repetition compulsion thereby becomes the tale of a continuous death and rebirth, the tale of the eternal return of an ego-consciousness that refuses to be annihilated and compulsively comes back to haunt its own death."112

"By repeating the impossibility of presence, the law of Eternal Return implies the inescapability of death."113

For Deleuze, within the repetition in eternal recurrence, "death does not appear in the objective model of an indifferent inanimate matter to which the living would 'return'; it is present in the living in the form of a subjective and differentiated experience endowed with its prototype... having renounced all matter, it corresponds to a pure form - the empty form of time."114

For Nietzsche, the "classical" is this "prototype." After Nietzsche's experience of eternal recurrence (itself a "classical" thought that returns through forgetting), repetition is an affirmation of recurrence, this emptying of time. Nietzsche's "classical" is also the repetition that masks, "which disguises itself in constituting itself, that which constitutes itself by disguising itself. It is not underneath the masks, but is formed from one mask to another, as though from one distinctive point to another, from one privileged instant to another, with and within all variations. The masks do not hide anything but other masks."115

The compulsive willed return of the "classical" past is a re-willing of its every detail: its (Apollonian) luminous immanence and intensity; its ethos of dread; its laws of fate as chance and repetition ("those iron hands of necessity which shake the dice-box of chance play their game for an infinite length of time: so that there have to be throws which exactly resemble purposiveness and rationality of every degree") - that compose the innocence of becoming of the "classical" abyss - the masked "deadly risk and secret" at the center of the labyrinth.116

THE SONG OF LOVE ERRING

Nietzsche, in considering the place of history within art (and architecture), speaks of the close proximity of death:

Art as conjurer of the dead - art incidentally

performs the task of preserving, even touching up extinct, faded ideas;

when it accomplishes this task it weaves a band around various eras, and

causes their spirits to return. Only a semblance of life, as over graves,

or the return of dead loved ones in dreams, results from this...118

This description, known by de Chirico and anticipating his "metaphysical" work, identifies the return of past times as that which haunts the "subject" of representation - rendering it always incomplete. Implicit is the dissolution of the telos of history in art - dis(re)membered history returns as a diminished death-effect (for "any high emotion is a death effect, a dissolution of the completed, of the historical").119

In de Chirico's work, history is no longer linear, a telos, but an ethos.120

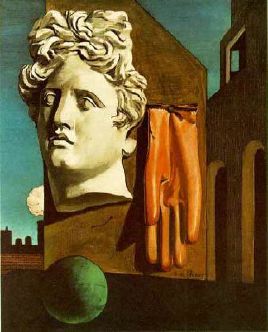

In The Song of Love, this ethos and death-effect is produced through an enigmatic and uncertain arrangement of discrete luminous objects - an architectural scene.121

De Chirico's work, as a "representation of humanity via its toys, constructions, sacred values, and mystery," exposes the artifice of history, the Nietzschean "purely aesthetic conception of history."122

Deliberately obscure objects, here the decapitated bust of Apollo, a glove, a ball, a wall, and a perspectival architectural fragment, radiate an "intensity of meaning with which children invest their playthings," and "living life 'sub specie aeterni' - under the aspect of eternity."123

Blanchot clarifies the difficulty of the continuity or singularity of the meaning of these objects: "not only is the image of an object not the sense of the object, and not only is it of no avail in understanding the object, it tends to withdraw the object from understanding by maintaining it in the immobility of a resemblance which has nothing to resemble."124

These objects are visual (and temporal) tropes. Here Nietzsche's grand style of classicism becomes the style/me that cuts the body (and architecture) into discrete impulses. The difficult and tenuous cohesion of the "subject," posited as telos, an identical historical continuity in representation (given the mark of permanence in stopped time), is simultaneously dis(re)membered. Both artifacts and their "subject" follow the logic of Nietzsche's "monumental history" to an extreme.125

They share "the danger that monumental history conceals, when it does not imply rupture" - "that of becoming somewhat distorted, beautified, and coming close to free poetic invention."126

The enframed scene of The Song of Love projects this enigmatic "subject" into the viewer through the complicity of architecture (on many levels) as disruptive effect. Here, as in the other paintings, there can be no single unified meaning, just as there cannot be a single unified "subject" of representation.127

Each interpretation further establishes the "subject" as incomplete; the subject's relation between architecture and history is simultaneously displaced and deferred. Consider the following (lengthy but incomplete) interpretations of The Song of Love:

_ As a chance set of objects, an oracular arrangement of objects in the permanence of chance, in painting, as signs to be interpreted

_ As a riddle of the origin of time, "the

beginning again in the absence of any beginning" and "the eternality

of the return, repeated infinitely by the fragmentary"128

1 This dissertation is sitting in the architecture library at the

Georgia Institute of Technology College of Architecture. A full PDF version,

excluding images, can be obtained from http://wwwlib.umi.com/dissertations/

, after filling in a few questions

(author's name Mical, dissertation number AAT 9912552).

2

tmical001@aol.com

3

Foucault, "Nietzsche, Genealogy, History," p. 140 in Tafuri, The Sphere and the Labyrinth, pp. 3-4.

Nietzsche, The Dawn, section 44 cited in Vattimo, "The End of Modernity: The End of the Project," p. 21.

Foucault, "Nietzsche, Genealogy, History," p. 143.

This Socratic time, an extension of the Socratic reason Nietzsche was opposed to, is implicated in Nietzsche's discussion in Twilight of the Idols, "The Problem of Socrates," section 10: "when one finds it necessary to make a tyrant out of reason, as Socrates did, then there must be no small danger that something else should play the tyrant. At that time rationality was surmised to be a rescuer... they had to make this choice: either to be destroyed, or - to be absurdly rational..."

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 283.

Taylor, Alterity, p. 246.

Derrida, Dissemination, p. 167 imbedded in Gasché, The Tain of the Mirror, p. 210.

The citation concludes in sinister though not inappropriate, language "...he subsequently intended this sublime trauma to be replicated in other people" in Waite, Nietzsche's Corps/e, p. 318. He continues examining this traumatic reading with terms such as "otherness, timelessness, outside the range of comprehension" only to reveal the source of this reading as contemporary scholarship on the Holocaust. The relation between eternal recurrence and the holocaust, identified in the works of Vattimo and alluded to in Blanchot's Writing the Disaster (perhaps) requires the mediation of Heidegger, and hence falls outside the scope of this work.

Klossowski, Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, p. 97. Significantly, it is Heidegger who relies on these unpublished notes to fabricate his interpretation of The Eternal Return of the Same, frequently as odds with the selectively published fragments Nietzsche wrote.

Klossowski, Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, p. 104.

Bataille, Visions of Excess, p. 220.

Klossowski, "Forgetting and Anamnesis in the Experience of the Eternal Return of the Same," p.148. Some critics have acknowledged indifference as an appropriate response if everything must repeat infinitely, specifically Ivan Soll: " the prospect of the infinite repetition of the pleasure or pain of one's present life entailed by the doctrine of eternal recurrence should actually be a matter of complete indifference" (Soll, "Reflections on Recurrence: A Reexamination of Nietzsche's Doctrine, die Ewige Wiederkehr des Gleichen," p. 339).

"Inner Experience," later the title of one of Bataille's books. See Taylor, Alterity, p. 144.

Hollier, "From Beyond Hegel to Nietzsche's Absence," in On Bataille (ed. Boldt-Irons), p. 70.

see Klossowski, "Forgetting and Anamnesis in the Experience of the Eternal Return of the Same," p. 139.

see Ibid., p.146.

Ibid., p.148

Kaufmann's introduction to Nietzsche, The Gay Science (trans. Kaufmann), p. 19.

Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, p.3. Kundera relies on the thought of Parmenides in evaluating the thought of eternal recurrence, with its great weight, as a negative in comparison with "the unbearable lightness of being." There is more to this simple retelling than meets the eye: Nietzsche, in his Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, first opposes Parmenides, first author of "being," in agon with Heraclitean (and Nietzschean) concept of "becoming" (pp. 70-1). Nietzsche then proposes to correct the Parmenidean error of "taking heavy and light, for example, light (in the sense of 'weightless') was apportioned to light, heavy to dark, and thus heavy seemed to him but the negation of weightless, but weightlessness seemed a positive quality" with the rebuke (significantly in corporal terms) "heaviness surely seems to urge itself upon the senses as a positive quality; yet this did not prevent Parmenides from labeling it as a negation" (pp. 71-2).

Taylor, Tears, p. 147

Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, p. 6.

Nietzsche, cited in Waite, Nietzsche's Corps/e, p. 328.

Nietzsche, in private correspondence to Overbeck, cited and translated in Löwith, Nietzsche's Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same, p. 87 and Nietzsche cited in Strong, Friedrich Nietzsche and the Politics of Transfiguration, p. 271.

Nietzsche cited without reference in Wood, "Nietzsche's Transvaluation of Time," p.46

Löwith, Nietzsche's Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same, p. 63.

Klossowski, Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, p.93.

The symmetry of this enigma lies in the homology of its structure, content, and effect. As an enigma, it reveals itself as the answer and origin of this enigma, nothing more. For an examination of these citations concerning Nietzsche's "great thought," see Strong, Friedrich Nietzsche and the Politics of Transfiguration, p. 262 and p. 268.

See for example, Kundera's brief explanation of the insubstantiability of something done once (einmal ist keinmal) in Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, p. 8.

Klossowski, "Forgetting and Anamnesis in the Experience of the Eternal Return of the Same," p. 140.

Ibid., p. 138.

Moles identifies the obvious Heraclitean and Stoic options, but adds a separate genealogy from Epicurus to Lucretius to Hume, who ridiculed it as "the most absurd doctrine ever conceived." Moles, in a footnote, identifies forty-four authors from antiquity to his contemporaries, all unknown to Nietzsche, and seventeen contemporaries that he may have known of, though of these only Blanqui is mentioned in his writings. See Moles, Nietzsche's Philosophy of Nature and Cosmology, p. 286 and fn. 7 on p. 405.

Klossowski, "Nietzsche's Experience of the Eternal Return" in The New Nietzsche, p. 108.

Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, book II section 1 cited in Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy, p. 113.

This initial citation concerning the ahistorical memory is from Magnus, Nietzsche's Existential Imperative, p. 38.

see Klossowski, "Nietzsche's Experience of the Eternal Return" in The New Nietzsche, p. 115.

Ibid., p. 282.

For a brief discussion of this Stoic "great year," see Eliade, Cosmos and History: the Myth of the Eternal Return p. 122.

Heraclitus, Fragment LXVI cited and translated in Robinson, Heraclitus, p. 45 and thereafter Kahn, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus, p. 273. Robinson notes: "if Heraclitus did believe in a periodic conflagration of the cosmos, a time-period for this may have been 10,800 years, what he apparently called a 'great year.' But so specific a conception may in fact be a Stoic importation, and should be treated with caution" (Robinson, Heraclitus, p. 101). Kahn's text does not support this caution (p. 158).

see Robinson, Heraclitus, p. 98.

Nietzsche, Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, p.62. Significantly (for this research) Nietzsche adds "The child throws its toys away from time to time - and starts again, in innocent caprice.... only aesthetic man can look thus at the world, a man who has experienced in artists and in the birth of art objects... how necessity and random play, oppositional tension and harmony, must pair to create a work of art,"

Heraclitus Fragment XCIX cited and translated in Kahn, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus, p. 75. See also Heraclitus Fragment CIII: "The way up and down is one and the same."

Heraclitus Fragment LXXIV in Kahn, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus, p. 63. See p. 190-2 for an examination of this enigmatic fragment.

Heraclitus Fragment LI cited and translated in Kahn, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus, p. 53.

Nietzsche, Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, p.51

Ibid., p. 54.

Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, p. 100.

Löwith, Nietzsche's Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same, pp. 109-10.

Erich Heller, "Nietzsche's Terrors: Time and the Inarticulate," p. 185.

These first two categories are discussed as seeking the ideal in every single case (lyrical) and tiring of this ideal and collecting curiosities (epic), though not initially explored in relation to the thought of eternal recurrence. See Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, p.201. Nietzsche's concern with the tragic appeared as the topic of his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, and would continue throughout his writings. The later move towards a purely Dionysian view of the world is here suspended to isolate the earliest "tragic" view of the classical he expounded, as it formed the basis for the Stimmung of de Chirico's "metaphysical" work.

Sloterdijk, Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche's Materialism, p. 20.

Ibid., p. 15.

Weiss, 'The Body Dionysian', p. 29

see Sallis, Crossings: The Space of Tragedy, p. 17.

Sloterdijk, Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche's Materialism, p. 25.

Goux, Oedipus, Philosopher, pp. 105-6. "Apollonian mimesis produces distancing images" (Sallis, Crossings: Nietzsche and the Space of Tragedy, p. 97).

Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, p. 17.

This fatality is not necessarily the fatalism of stoic recurrence, but Nietzsche's "existential imperative" to make any move as if you would have to repeat it an infinite number of times. Concerning the significance of the eternal recurrence as composed of loops and coils, see Wood, "Nietzsche's Transvaluation of Time," pp. 40-1.

"As Walter Kaufmann points out in his translation of Beyond Good and Evil, this Latin sentence is ambiguous. It can mean: 'A vicious circle is made god.' Or: 'God is a vicious circle.' Or "The circle is a vicious god.' - translators note in Löwith, Nietzsche's Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same , p. 261. This term also forms the core argument of Klossowski's writings on Nietzsche's eternal recurrence.

Klossowski, Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, pp. 30 and Klossowski, "Forgetting and Anamnesis in the Experience of the Eternal Return of the Same" p.148 and finally Klossowski, Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, pp. 55-6.

Blanchot, Le Pas au Dela, p. 49 cited and translated in Taylor, Alterity, p.239

Scott, "Masks of Self-Overcoming," p. 221.

Blanchot, Writing the Disaster, p. 2.

Nietzsche, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, has Zarathustra speak against his dwarf that time conceived as a circle is too simple an image. This caveat is sustained in many close readings of this text. See for example Hatab, Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: the Redemption of Time and Becoming, pp. 94-5 and Stambaugh, The Problem of Time in Nietzsche, p.174.

Klossowski, "Nietzsche's Experience of the Eternal Return," pp. 113-4.

Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy, p. 48

see Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, p. 104.

Bataille, Inner Experience, p. 154 in Hollier, "From Beyond Hegel to Nietzsche's Absence," p. 69.

Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, "Of the Vision and the Riddle;" this synopsis continues without citation from this primary source.

In a provocative fragment, Nietzsche writes "since Copernicus, man rolls from the center into an X." This unpublished fragment, and its relation to Nietzsche's analysis (in Löwith, Nietzsche's Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same , p. 52) of nihilism would (perhaps) take us outside our genealogy. Nihilism's relation to eternal recurrence made most explicit in the posthumous collection of fragments published as Nietzsche's The Will to Power.

Moles, Nietzsche's Philosophy of Nature and Cosmology, p. 224.

Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, pp. 23 and 46.

Magnus, Nietzsche's Existential Imperative, p. 154; Stambaugh, The Problem of Time in Nietzsche, p.180; and Wood, "Nietzsche's Transvaluation of Time," pp. 40-1. Stambaugh's influential analysis of the problem of time in Nietzsche's thought of eternal recurrence is here used to articulate the crossing of the horizontal and vertical axes of time in the experience and thought of eternal recurrence.

Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, p. 108. Though these possibilities are examined in his unpublished writings, it is significant that the necessary concept of eternity inherited from the classical predecessors of eternal recurrence remains an unstable identity; a difficult thought crossed with the possibility of the moment of insight of recurrence, itself a difficult to articulate, as we have seen.

Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, pp. 125 and 114.

Moles, Nietzsche's Philosophy of Nature and Cosmology, pp. 295-6.

Wood, "Nietzsche's Transvaluation of Time," p.42.

Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, p. 117 and Magnus, Nietzsche's Case: Philosophy as/and Literature, p.29.

Wood, "Nietzsche's Transvaluation of Time," p.41

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p.11.

Nietzsche cited and translated in Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, p. 197.

Hatab, Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: the Redemption of Time and Becoming, p. 99. Repetition and "its dark precursor" (see Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p.291) as both the content and form of the doctrine of eternal recurrence, and anticipates the use of repetition in the itinerary of De Chirico's architectural representations.

Stambaugh, The Other Nietzsche, p. 85.

Klossowski, "Forgetting and Anamnesis in the Experience of the Eternal Return of the Same," p. 145. The observation continues: Ruse which removes from the event its 'once and for all' character: such is the subterfuge that the Sils Maria experience (unintelligible) in itself first offers to reflection: the latter is in this way centered on the will."

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 6.

Irigaray, Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche, p. 11.

Löwith, Nietzsche's Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same, pp. 170-1.

Ibid. p. 170.

Hatab, Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: the Redemption of Time and Becoming, p. 106

Blanchot, The Infinite Conversation, p. 271.

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 90. Deleuze reads the polyvocal status of repetition within recurrence through the supplement of Freudian repetition, and to a lesser degree Marxist, not as competing thoughts, but as a scaling of regimes of thought.

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 7.

Ibid., pp. 294 and 295.

Ibid., p. 105 and 295.

Ibid., p. 108.

Ibid., p. 201.

Ibid., p. 201.

Ibid., p. 297.

Ibid., p. 90.

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, pp. 2-3. Deleuze continues, in terms appropriate for the three genealogies in de Chirico's work: "It puts law into question, it denounces its nominal or general character in favor of a more profound and more artistic reality."

The alterity is posited on the discrepancy between two identical events, one present and one locked in the past; this anamorphic thinking of signification, a "Doppler effect" is produced by the selfsame event in discretely separate times, significant to thinking the repetition and return.

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 7.

Repetition as a tendency to "repeat repressed material as a contemporary experience" (transference neurosis) is opposed to "remembering it as something belonging to the past." (Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, p.19). This text, coming after Nietzsche's writings and in a suspicious state of professed ignorance of Nietzsche, is paramount in Deleuze's analysis. It is included here, not to drag the whole deterritorializing apparatus of Freudian analysis to de Chirico (as Foster in Compulsive Beauty has done), but to specifically and narrowly reiterate the significant origin (and identical conclusion) of repetition.

Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, p. 37.

Tafuri and Teyssot, "Classical Melancholies," p. 25. The repetition in its synecdoche is explained: "this figure of speech, which is a form of metonymy and which, if we believe the entomologists, corresponds to the way in which ants see things, invests the part with authority to indicate the whole."

Chapelle, Eternal Recurrence: A Psychological Essay on the Compulsive Return of Fixed Experience Patterns, p.155.

Ibid., p. 162.

Ibid., p. 165.

Nietzsche cited and translated in Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, p. 197.

see Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, pp. 41-5.

Chapelle, Eternal Recurrence: A Psychological Essay on the Compulsive Return of Fixed Experience Patterns, p. 232.

Taylor, Alterity, p. 241

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 112.

Ibid., p. 17.

Nietzsche, KSA III, p. 122 cited and translated in Babich, Nietzsche's Philosophy of Science, p. 161. Knesl writes: truly classical architecture is a symbol that holds out a threatening but also life-giving challenge, presents a deadly risk and secret"" in Knesl, "Architecture and Laughter," n.p.

117 image from http://www.geocities.com/Athens/6163/love.html

; original is held by the Museum of

Modern Art, New York.

118

Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, section 147

This death-effect, identified here by Lyotard in relation to eternal recurrence, is significant in pairing the completed with the historical, as if each term duplicates the other, both dissipated in the high emotion of eternal recurrence. See Lyotard, "The Return and Kapital," p.51.

This ethos, extending from the "stimmung" (atmosphere in a moral sense) is identified first by Cocteau, who noted his interest not in De Chirico's aesthetics, but ethics. See Cocteau, "Giorgio De Chirico," p. 103 and Rainbow-Vigourt, The Vision of Giorgio de Chirico in Painting and Writing, p. 307 fn. 473.

Any of De Chirico's "metaphysical" paintings could stand within this definition - this specific work will be utilized to illustrate the Nietzschean relation of history to art (and architecture) within De Chirico's oeuvre.

Rainbow-Vigourt, The Vision of Giorgio de Chirico in Painting and Writing, p.260 and Hayden White, Metahistory, p. 373.

Soby, The Early Chirico, p. 33, and Moles, Nietzsche's Philosophy of Nature and Cosmology, p. 244. Moles comment, an examination of this classical concept in relation to eternal recurrence in Nietzsche's thought, inserted here describes the persistence of these classical forms in The Song of Love as a question of time and recurrence, and proposes the aspect of eternity that is the death-effect of De Chirico's classical fragments (outside teleological reason).

Blanchot, The Space of Literature, p. 260

Nietzsche identifies monumental history as "the great moments in the struggle of the human individual constitute a chain, that this chain unites mankind across the millennia like a range of human mountain peaks, that the summit of such a long-ago moment shall be for me still living, bright, and great." Nietzsche writes the "present man... learns from it that the greatness that once existed was in any event once possible and may thus be possible again." Written in 1874, eight years before the thought of eternal recurrence, Nietzsche goes on to describe the only possibility of such a repetition in words strikingly similar to the early Greek notion of eternal recurrence: "that which was once possible could present itself as a possibility for the second time only if the Pythagoreans were right in believing that when the constellation of the heavenly body is repeated the same things, down to the smallest event, must also be repeated on earth: so that whenever the stars strand in a certain relation to one another a Stoic again joins with an Epicurean to murder Caesar, and when they stand in another relation Columbus will again rediscover America. Only if, when the fifth act of the earth's drama ended, the whole play every time began again from the beginning, if it was certain that the same complex of motives, the same deus ex machina, the same catastrophe were repeated at definite intervals, could the man of power venture to desire monumental history in full icon-like veracity, that is to say with every individual peculiarity depicted in precise detail... " (Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, "On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life," section 2 - italics mine). Here the connection between monumental history, eternal recurrence, and icon-like catastrophic intervals implicit in De Chirico's work is here made explicit. Significantly, Nietzsche goes on to describe the effect of such a monumental history, its "effects in themselves," recognizing the disruptive effect of eternal recurrence long before the idea came to him. This production of effects from pure monumental history, alluded to in The Song of Love, cannot be overstated.

Lacoue-Labarthe, "History and Mimesis," p. 226. A similar sentiment concerning Nietzsche's revaluation of history by White is: "The important point is that the historical field be regarded, in the same way the that the perceptual field is, as an oscillation for image-making, not as a matter for conceptualization." (Hayden White, Metahistory, p. 372).

In that the pictorial subject is uncertain and enigmatic, it projects this uncertainty into the subject it constructs visually that the viewer steps into when viewing this (or any) work. "Subject" here indicates this double-image, both the meaning of the painting and the viewer it constructs. In this work, the multiplicity of one destabilizes the unity of the other.

Nelson, Maurice Blanchot: The Fragment and the Whole, p. 58.

129

Blanchot, The Space of Literature, p. 231.

130

Abel, "George Bataille and the Repetition of Nietzsche" in On Bataille, p.54

131

Bataille, Visions of Excess, p. 207.

132

Nelson, Maurice Blanchot: The Fragment and the Whole, p. 47.

133

Stambaugh, he Problem of Time in Nietzsche, p.192

134

De Chirico, "Eluard Manuscript" in Hebdomeros, p. 180.

135

Lacoue-Labarthe, "History and Mimesis," p. 226.

136

Knesl, "Laughter of the Gods," n.p.

137

Nietzsche, The Gay Science, section 109

138

Schrift, "Foucault and Derrida on Nietzsche," p. 137.

139

Julian Young, Nietzsche's Philosophy of Art, p. 39.

140

Blanchot, The Space of Literature, pp. 217-8.

141

Stambaugh, Nietzsche's Thought of Eternal Return, p. 10.

142

See Miller, "Dismembering and Dis(re)membering," p. 50:

143

De Chirico, "Statues, Furniture, and Generals" in Hebdomeros, p. 243.

144

De Chirico, "Eluard Manuscript" in Hebdomeros, p. 187.

145

Contrast this to Tafuri's self-described project: "not to forge history, but rather to give form to a neutral space, in which to float, above and beyond time, a mass of weightless metaphors" (Tafuri, The Sphere and Labyrinth, p.15). The multiple meanings of the word forge in this context are significant. The discrete separation of event and meaning in history in this context should both function like De Chirico's enigmatic artifacts and their meanings. Tafuri is not proposing something entirely different, though he continues with a discussion of the limits of language, implicit in this discussion. The contrast between weightless metaphors and De Chirico's semiosis are both necessary within a Nietzschean perspectivism. In both cases, it is a question of selection that prevents the proliferation of interpretations from approaching a totality, a totality conceptually impossible in perspectivism.

146

Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, section 2

147

This notion of erring is indebted to Taylor's Erring: A Postmodern A/theology. See pp. 11-12 for an etymology of the word erring, concluding with "the semantic branches of err spread to errancy, erratic, erratum, erre, erroneous, and errant."

148

Taylor, Erring: A Postmodern A/theology, p. 151. Taylor concludes this description of the subject, in words reminiscent of Nietzsche's "monumental history," with "the unhappy subject is forced to acknowledge the undeniable transcendence of the 'ought.'"

149

Nietzsche, The Gay Science, section 110

150

Hayden White, Metahistory, p. 332. Though most of White's analysis of Nietzsche is contradicted by the writing, the tenuous assertion here is supported by the above citation from Nietzsche.

151

See Lacoue-Labarthe, The Subject of Philosophy, p. 6.

152

Derrida, Spurs: Nietzsche's Styles, p. 89.

153

This citation, from Blanchot, The Space of Literature, pp. 242-3 is presented in relation to Rilke's work, but specifically situates the death-effect of repetition, eternal recurrence, and the origin of art within this void. It is here widened to include the void left in the place of history in the work of art, thought it implicates also the blocked access to a metaphysical other-world that comprises De Chirico's work, the void behind representation, eternal recurrence as the concealed portion of enigmatic architecture, and countless other absences possible within De Chirico's paintings.

154

Following this Nietzschean critique of teleological (historical) truth, this reading, and all others, err.

155

Vattimo, "The End of Modernity," p. 60.

156

Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, sect. 5

157

De Chirico, "Eluard Manuscript" in Hebdomeros, p. 184. Note the hesitancy in identifying a truth in De Chirico's words, here the only time the word is used in the writings contemporaneous with the "metaphysical" paintings of 1911-17. The privileging of this effect of silent terror over rationally constructed truth is enhanced by the following text, "but such truths do not talk, they have no voice; still less do they sing; but sometimes they look at one, and at their glance one is forced to bow one's head and say, yes, that is true. What results - a picture, for example, always has a music of its own; that is inevitable, that is the mysterious destiny of all things to have a thousand souls, a thousand aspects" (p. 184).

158

This history that searches for origins through repetition, not exegesis, is inseparably bound to the question of fatality and death.

159

Hollier, Against Architecture, p. 55.

160

Grassi, Architecture Dead Language, p.139

161

Repetition that facilitates the escape from telos overturns the diachronic through analeptic suspensions, back-wards looking scenes that are dischronic, not synchronic.

162

Nietzsche writes in "The Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life" (section 1) of the unhistorical animal "it is contained in the present, like a number without any awkward fraction left over; it does not know how to dissimulate, it conceals nothing and at every instant appears wholly as what it is... man, on the other hand, braces himself against the great and ever greater pressure of what is past.... death at last brings the desired forgetting."

163

Nietzsche, writing of the necessity of incompletion in art, turns towards this precedent: "incompleteness as an artistic stimulation - incompletion is often more effective than completeness, especially in eulogies... completion has a weakening effect" (Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, section 199).

164

Fynsk, "Crossing the Threshold," p. 73.

165

Gasché, "The Felicities of Paradox," p. 52.

166

Blanchot, The Gaze of Orpheus, p. 43.

167

After Cicero, the panegyric mode of rhetoric (in Greek epideictic) is proper to funerals, as a balancing of (ethical) accounts.

168

Taylor, Erring, p. 151.

169

Taylor, Erring, p. 153. This description of the narrative tripartite historical schema of "creation, fall, redemption" in Taylor's work is challenged with the concept of alterity (erring, estrangement) that negates the power of origins and ends, and especially teleological thought. De Chirico's exposure of suppressed origins, as that which must return, appears to follow this structure, yet the presence of repetition (finite and infinite) is the disruptive cause of ateleological thought. Repetition, as considered in Freud's Beyond the Pleasure Principle, as a tendency towards an originary (fatal) state, problematizes any simple historical schema. The suppressed origin of history in death return in every repetition in De Chirico, as both panegyric and alterior "history," with loss at the transparent center.

170

Klossowski describes the effect of eternal recurrence as a "new fatality" he names the "vicious circle," "which suppresses every goal and meaning, since the beginning and the end always merge with each other" (Klossowski, Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, p. 30).

170

Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 112. Deleuze here utilizes Blanchot's writing about death within language to understand the death within repetition. He cites Blanchot on the second aspect of death, the impersonal that is the risk of the personal: "it is inevitable but inaccessible death; it is the abyss of the present, time without a present, with which I have no relationships; it is toward which I cannot go forth, for in it I do not die, I have fallen from the power to die. In it they die, they do not cease, and they do not finish dying..." (Blanchot, The Space of Literature, pp. 106, 154-5).

171

De Chirico, "Eluard Manuscript" in Hebdomeros, p. 186.

172

The full Blanchot citation concerns specifically the work of art "in the work of art the gods speak, in the temple the gods dwell, but disguised, but absent... the work utters the gods, but utters them as unutterable, it is the presence of the absence of the gods and, in this absence, it tends to become itself present, to become no longer Zeus, but a statue... and when the gods are overthrown, the temple does not disappear with them, but rather it begins to appear, it reveals itself by continuing to be what before it was only unknown to itself: the dwelling-place of the absence of the gods" (Blanchot, cited without reference in Teyssot, "Fragments of a Funerary Discourse," p. 13). The language of this text recalls clearly the "metaphysical" works of De Chirico.

173

Taylor, Erring, pp. 154-5. Taylor's description of this alterior history presupposes an acknowledged relation between "the death of God, the disappearance of the subject, and the ends of history" (p.154), a relationship derived partially from Nietzsche's insights, and relevant to the question of the place of death within architectural history painted by De Chirico.

174

Teyssot, "Funerary Discourse," p. 6.

175

Erich Heller, "Nietzsche's Terrors: Time and the Inarticulate" in The Importance of Nietzsche, p. 178.

176

See Loraux, Tragic Ways of Killing a Woman, p. 49.

177

Teyssot, "Funerary Discourse," p. 6.

178

The arch as proto-type duplicates the Nietzschean gateway as an enigma of fatality, and is here always present in De Chirico's representations of architecture. Outside of the constraints of functionalism, they propose a compelling question of their signification, and death as a type is intended to describe this network of relations.

Kofman proposes a reading of Nietzschean (monumental) history that replaces the "evolutionary" model of history with a "typological" one utilizing Nietzsche's privileging of the Presocratic philosophers: "the Presocratics belong to a rare type; they are irreducible to any other. To reconstitute their image, it is best to 'paper the walls with them a thousand times'"" (Sarah Kofman, "Metaphor, Symbol, Metamorphosis" in The New Nietzsche, p. 212). De Chirico's history is here also typological, and death is the originary apparatus.

179

Rossi, Scientific Autobiography, p. 2.

180

see Grassi, Architecture Dead Language, p.135

181

This observation is from Soby, The Early Chirico (p.38); it is left unexplored in the text, and occurs in relation to the painting Melancholy of Departure. This effect is not localized to this painting, but the majority of De Chirico's work.

182

Bataille, Visions of Excess, p. 216.

183

See Kofman, Nietzsche and Metaphor, pp. 66-7. Nietzsche uses the metaphoric Roman columbarium to illustrate the complete exhaustion of logical systems of classification, contra his perspectivism: "whereas each perceptual metaphor is individual and without equals and is therefore able to elude all classification, the great edifice of concepts displays the rigid regularity of a Roman columbarium and exhales in logic that strength and coolness which is characteristic of mathematics. Anyone who has felt this cool breath will hardly believe that even the concept... is merely the residue of a metaphor, and that the illusion which is involved in the artistic transferal of a nerve stimulus into images is, if not the mother, then the grandmother of every single concept." (Nietzsche, Philosophy and Truth, p. 84 cited and translated in Kofman, Nietzsche and Metaphor, p. 68).

184

Kofman, Nietzsche and Metaphor, pp. 67. The Roman concept of memory as a treasure-house is inverted in the columbarium, where the grid equalizes all lives as indiscriminate ashes. Nietzsche's use of ashes to signify the exhaustion of metaphors into rigid concepts situates the columbarium as the epitome of perspectival reason, contra De Chirico's architectural dead language that situates the possibility of death within near-anamorphic fatal arcades.

185

This assertion by Blanchot is the thesis of The Infinite Conversation, and this assertion is examined in Nelson, Maurice Blanchot: The Fragment and the Whole, pp. 17-20.

186

Maudemarie Clark, Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy, p. 279.

187

Lacoue-Labarthe, The Subject of Philosophy, p. 4. Lacoue-Labarthe is here examining the Hegelian notion of the end of history through the critique of Nietzsche, specifically by undercutting the "metaphysical" assumptions in teleological history. Nietzsche's eternal recurrence erodes the sanctity of origin and end, positing them as possible identities.

188

Foucault, "Nietzsche, Genealogy, History," p. 143.

189

Nelson, Maurice Blanchot: The Fragment and the Whole, pp. 34 and 17.

190

Blanchot, The Infinite Conversation, p. 272.

191

Lacoue-Labarthe, "History and Mimesis," p. 226. Lacoue-Labarthe argues in this essay that the whole German operation of consigning history to philosophy is most clearly articulated in Nietzsche's "The Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life." This depiction of the result of Nietzsche's explorations of the philosophy of history follows closely the historical-informed visual rupture that De Chirico proposes in his "metaphysical" work.

Lacoue-Labarthe concludes "historical mimesis, such as Nietzsche conceives it, does not consist of repeating the Greeks but of recovering the analogue of that which was their possibility: a disposition, a force, a power - the capability of extracting oneself from the present..." (p.227). For an examination of this mimesis and alterity in relation to the historical identity of the architectural "subject," see Conclusion, Section 4 "The Histrionic Architectural 'Subject': A Counter-Memory."

192

Crary, Techniques of the Observer, p. 3. In Crary's argument, after Nietzsche "modernity, in this sense, coincides with the collapse of classical models of vision and their stable space of representation" (p.24).

193

Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, p. 139.

194

With the affirmation of the eternal recurrence, both possibilities are deprived of their place within a teleological - their persistence or suspension in repetition speaks of this loss of history, and their persistence is the persistence of the enigma of architecture's dead language at the closure of history.

195

Blanchot, The Infinite Conversation, p. 417.

196

Tracy Strong, Friedrich Nietzsche and the Politics of Transfiguration, p. 137.

197

For a discussion of Nietzsche's emphasis on the Delphic oracle's place in the emergent classical culture (originally posited in "On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life," section 10) see Tracy Strong, Friedrich Nietzsche and the Politics of Transfiguration, p. 138.

198

Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy, p. 107.

199

Tejera, in Nietzsche and Greek Thought, discusses the classical figure of Janus dikranoi palintropos in relation to Nietzsche's historical thinking (p. 50).

When Nietzsche, in considering the projection of the classical (tragic) into the modern in The Birth of Tragedy, writes "Scholarship, art, and philosophy are growing together inside me to such an extent that one day I'm bound to give birth to centaurs" (Letter to Erwin Rohde, in Nietzsche: A Self-Portrait from his Letters, p. 10 cited and examined in Sloterdijk, Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche's Materialism, p. 11), this untimely double-figure, half man and half animal (both classical and modern) marks the insight of Nietzsche's larger project: "suddenly, Greek antiquity was no longer a faithful mirror for humanistic self-stylization, nor a guarantee for reasonable moderation and proper bourgeois serenity. In one stroke, the autonomy of the classical subject was done away with. From above and from below, from the numinous and the animal realms, impersonal powers broke into the standardized form of the personality and turned it into a tumbling mat for dark ands violent energies, an instrument of anonymous universal forces" (Sloterdijk, Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche's Materialism, p. 14).

For a discussion of Nietzsche's centaur as the hybrid textual style of the classical reciprocated with the modern, and Nietzsche's own later critique of this style, see Silk and Stern, Nietzsche on Tragedy, p. 122.

200

The term palintropos from Heraclitus is a "back-turning' that implicates the "back-stretching" of the double-figure of the bow, discussed in relation to Apollo (see Kahn, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus, pp. 195-9). The atelological classical suspended in visual tension with the modern is a type of this stretching or turning, (which also is a form of troping). The origin and end of both epochs is here posited as identical.

201

Löwith, Nietzsche's Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same, p. 9. Löwith subsequently discusses "Nietzsche's repetition, on the peak of modernity, of the ancient view of the world" in relation to the overcoming of nihilism (p. 156).

202

Boothroyd, "Nietzsche's Future Perfect and the Eternal Return: Toward a Genealogy of Ideas," p. 129.

203

Mouw, The Tragic Insight and the Economy of Sacrifice: Nietzsche, Dionysus, and the Death of God, p. 40.

204

De Chirico, "Eluard Manuscript" in Hebdomeros, p. 190.

205

Strong, Friedrich Nietzsche and the Politics of Transfiguration, p. 283.

206

Taylor, "Nuclear Architecture..." , p. 17.

207

Knesl, "Laughter of the Gods," n.p. See also Hersey, The Lost Meaning of Classical Architecture, p.44, in which he cites Nietzsche's revaluation of classical architecture: "but taboo is not just a question of attraction and repulsion; the dangers and blessings involved are so powerful that the actions to be performed can only be approached with the most extreme ceremony. Let us note that the classical orders are similarly beset. This I believe is what Nietzsche meant when he described 'the atmosphere of inexhaustible meaningfulness' that hung about the ancient temples 'like a magic veil...the basic feeling of uncanny sublimity, of sanctification by magic or the gods' nearness...the dread [that] was the prerequisite everywhere."

208

Taylor, Alterity, p. 240.

209

Taylor, Tears, p. 81.

210

Blanchot, The Space of Literature, pp. 244 and 257 cited in Taylor, Alterity, p. 246.

211

Foucault, "Nietzsche, Genealogy, History," p. 154.

212